A father and daughter are helpless in their grief in Hossein Molayemi and Shirin Sohani’s shortlisted animated film, In the Shadow of the Cypress. It feels like the sea will take them away at any moment as they wade through their unspoken sadness. When an unbelievable circumstance forces this pair to confront their emotions, it takes them to depths beyond their wildest expectations.

**We have linked In the Shadow of the Cypress below. Take some time to watch the film and then scroll back up to read our interview.**

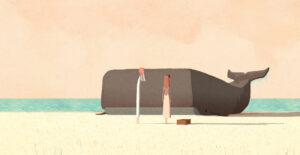

A Captain lives by the sea with this daughter, but a tragedy is dampening their relationship. The trauma of losing The Captain’s wife sends him to traumatic places where he harms himself, broken glass littering every surface of their home. When a whale becomes beached just outside their home, The Daughter rushes to save it even though it seems impossible.

When you watch this animated short, you can feel how personal it is. There are films that attempt to tap into the deepest corners of depression and desolation, but if it doesn’t come from a genuine exploration, it feels artificial. That is not the case with Molayemi and Sohani’s piece.

“At first, we knew that we wanted to make a film about the importance of family,” Sohani began. “That was our goal. We wanted to explore some challenges that Hossen has with his father in their relationship and also the story of my father during the war. He was a veteran and he lost one of his eyes in the Iran-Iraw war while he was training to be a pilot, and, at that time, it was vital for him to keep his eyes healthy. He was suffering from the side effects of the medicine that he was using, and it was similar to someone who is suffering from PTSD. That behavior is one of the inspirations of our film. At first, we chose the father and his son, and his son was playing an instrument. Then we changed the location of this story to the South of Iran, which is the Persian Gulf, and then it changed because of some of the beautifil elements came into it like with the sheep, the whale, and the sea.”

The physical design of the characters is striking in its size. The Captain’s legs and arms are about as thing as the cigarettes he smokes while the whale is square, block-like, and feels heavy. The directors reveal some of their challenges that influenced these choices in design.

The physical design of the characters is striking in its size. The Captain’s legs and arms are about as thing as the cigarettes he smokes while the whale is square, block-like, and feels heavy. The directors reveal some of their challenges that influenced these choices in design.

“One of our biggest challenges, in all honesty, was making money to make it,” Molayemi says. “We are living in a country under heavy sanctions, and we have to manage our resources very carefully. We decided to stylize our visuals and the designs of the characters in a geometric way so we could simplify it. Despite it being a less expensive way to animate it, it was still appealing to the audience. That was a challenge. Pete Doctor told us that he felt a kinship between our work and the Cartoon Saloon movies, but that was not intentional. We didn’t want to imitate any certain style or any studio.

The thinness of the father actually implied his weakness and his lack of ability to support his daughter. The curve-like body of the father is actually similar to the cypress trees in Persian miniatures, if you pay close attention. A lot of our animators had emigrated fro Iran, because of these sanctions. The simplified style helped us to complete the film with less animators.”

“A lot of animators are living in Iran, but they left their professional job since they cannot make a living,” Sohani adds. “Some are suffering with depression, and they are no longer able to make a piece of art since their energy is so low.”

The majority of the film is bathed in warm beiges, maroons, and browns. The sand beneath their feet is a speckled canvas. When The Captain is forced to look inward to his trauma, the palette changes in the most startling way, utilizing deep midnight blues and blood reds. It’s almost as if he doesn’t want his pain to seep out into the rest of the world, because it’s too intense.

“I had a strong feeling that these palettes were going to be appropriate for this story,” Sohani says. “Regarding the inner world of the father, we knew that it had to be completely different from the real world. For our story, the deep blue symbolizes sadness and depression, and we thought it could represent the PTSD patients. Maybe choosing this palette shows that we aren’t disappointed about these peoples’ lives. Subconsciously, we wanted to show the light even while we watch a very sad story. We wanted to show the audience some hope through the colors through the beginning. We can find love through this story.”

“In the first three-quarters of the film, we didn’t want to imply too much hope,” Molayemi says. “The challenge we had to choose warm colors because of the intense heat of the sun. It was contradictory to the atmosphere that we wanted to establish, inside the father’s mind.”

When the father and daughter have to enter the water at the end, we are left questioning how this bond will go on moving forward. Did The Captain succumb to the sea? Will their paired loss be broken apart now that the whale has made it back to sea? There is a shot from below the water’s surface where we are looking up and The Captain is floating in the shape of a ship’s anchor. The uncertainty is welcome.

“We wanted this kind of ambiguity at the end,” Molayemi says. “Maybe we have our own opinion about whether or not the father is alive or dead, but we wanted this uncertainty. I think it depends on the audience, what they take from it.”

“The last shot before the ending, the daughter is rowing, and you can see her face coming out from the shadows into the light,” Sohani says. “The status of the father, in our opinion, is not that important. What the father did for the daughter matters the most, and the camera doesn’t follow the whale as it passes by.”