Academy Award-nominated Sugarcane directors Emily Kassie and Julian Brave NoiseCat reveal why their doc is a “reverse Western” and how they captured footage the Vatican didn’t want you to see.

National Geographic’s Sugarcane is a remarkable documentary achievement unearthing stories of abuse at St. Joseph’s Mission, and as a film itself, it’s also a marvel. Beautiful cinematography and careful editing help center the survivors, even in the opening credits.

‘We felt very strongly that these were people worthy of epic storytelling,” says co-director Emily Kassie. “They were characters who were smart, strong, and courageous, and this was about them and their POVs through this moment of reckoning. One of our editors Maya Daisy Hawke said, ‘Let’s give them a title sequence worthy of the big screen.’ Before that title sequence, Jules and I talked about this being a reverse Western. A stranger comes to town, and events start unfolding.”

That stranger in the film is, of course, co-director Julian Brave NoiseCat, who shows up in Williams Lake with questions about his father’s life. The first image we see is of NoiseCat on the phone, his back to the camera, ready to find answers.

“The history of film and documentary in particular has not been kind to Indigenous peoples,” says NoiseCat. “And in many ways, the beauty of the cinematography and the way we portray our subjects is a direct refutation of that history as well as the history of cultural genocide of these institutions. Hollywood was built on Westerns that portray native people dying at the other end of frontiers and fake guns, and ours is a film about people who are still living despite all that and living in a very beautiful way.”

Archival Footage: Black and White Ghosts Telling The Story

In addition to thinking about the doc as a Western, Kassie and NoiseCat infused historical footage from the mission into the film, acting as recollections for the survivors, black and white ghosts returning to tell their story.

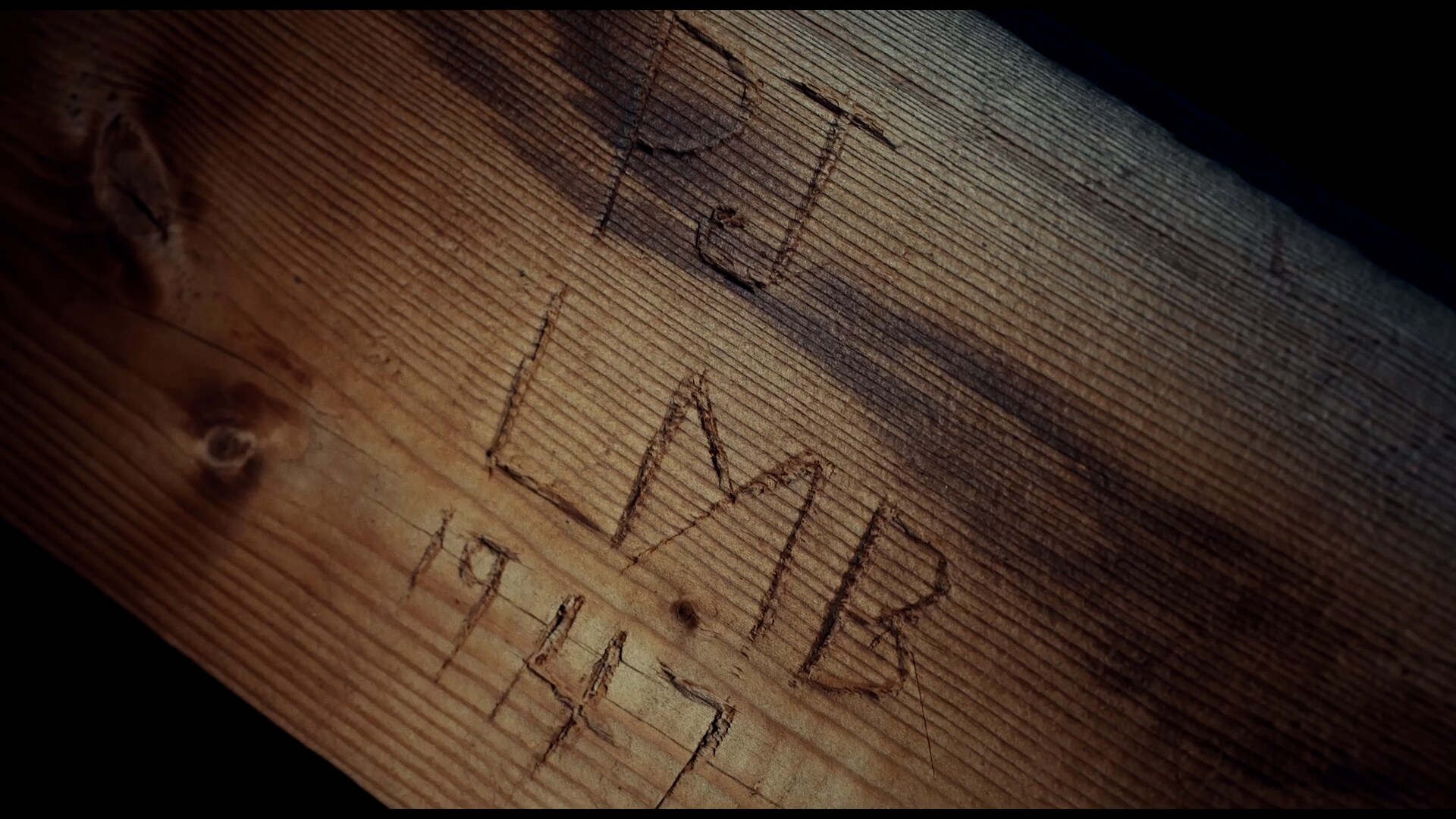

“We really wanted to use archival as memory,” says Kassie. “That evolved over time. There’s a search for the souls on the grounds of St. Joseph’s Mission that are etched in the walls of the barn. What does it mean to move between the past and present with our characters?”

And while the footage proved to be a valuable storytelling tool, it also served as a reminder of the mission’s intentions.

“These are documentaries that were propaganda that ran on the CBC and justified this program of cultural genocide,” continues NoiseCat, “beamed into televisions across Canada, replete with ads where you could adopt native children. We thought a lot about how we wanted to use it both in a creative and different way that would be true to the vérité format while saying something about that material and part of the broader ideology of these schools.”

“We Did Not, And Still Do Not, Talk About This History”

When Pope Francis invites Indigenous abuse survivors to the Vatican for an apology, Williams Lake First Nation Chief Rick Gilbert shares his abuse with a priest during the trip. The camera sits on him for quite a while after his admission.

“In this moment, he musters this courage within himself to say the truth,” says Kassie. “Everything you need to know about his emotional journey comes up in his face, so it was my job to hold there as long as possible. When we got to the edit, the shot kept going. The question was how long can we hold in those silences? Thematically, the silences were so important because these are not only stories that were hidden and repressed by the church and the government but within Indigenous communities and survivors themselves.”

After news hit of the discovery of unmarked graves at Kamloops, NoiseCat says a common refrain he saw in the media was how Indigenous people had been talking about this history but people had not been listening.

“When I heard that, it did not ring true to the family and community I come from,” says NoiseCat. “We did not, and still do not, talk about this history. That suppression and silence of that history isn’t just something that exists in broader colonial and Canadian and American society, but as colonization works, it also had been internalized by us ourselves as partially a way to survive and cope with this painful effort to eliminate our culture and tear apart our families.”

“The Truth is, Megan, I Snuck into the Vatican”

Even though the Vatican invited Indigenous survivors to Italy for an apology, there was one big stipulation that Kassie and NoiseCat had to work around for the film.

“They didn’t allow any independent media in, any media other than their own Vatican channels, to document [the apology],” says NoiseCat. “I think that says so much about that institution and its intense need to control the narrative.”

While the duo tried to receive access through the normal channels, they knew this experience needed to be documented, whether they had permission or not.

“Through a series of choices, I’ll just say, the truth is, Megan, that I snuck into the Vatican and skirted the Vatican guard,” says Kassie. “I got into that room and was able to witness Rick in this historic moment.”

Kassie describes the scene as one of confusion and disappointment, with the Pope speaking Italian to a room full of Indigenous people from all over North America in their traditional regalia who did not.

“And then at the end, he says, ‘Pray for me, I’ll pray for you. Bye, bye,” she continues. “He walks off, and the feeling was, what just happened? I think everyone knew they had witnessed something historic, but there was also a feeling of deflation, particularly for Rick.”

Bookended with the Vatican’s apology is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s half-hearted attempt to the Indigenous people, which was also in a foreign language (this time ceremonial French).

“This gets at the performative nature of these apologies for lack of a better term,” says NoiseCat. “That inherently raises a question of how substantive are they. What would it mean to really say you’re sorry? I think Rick hits the nail on the head when he said the Catholic Church has never paid its share. Just like the church didn’t let us in to film the apology, they still refuse to open their records. They’re clearly willing to apologize for the actions of specific members, but not by the church as an institution.”

Sugarcane is streaming on Hulu.