The relationship between a cinematographer and a director on television or film can be mercurial. On the great FX show The Old Man, starring Jeff Bridges, cinematographer Jules O’Loughlin worked on episodes 1, 3, 5, and 7. Director Ben Semanoff worked with Jules collaborated with Jules on episode 5, which is like no other episode in the season. While much of The Old Man season two is shot in wide open spaces or constantly on the move, episode 5 is shot almost entirely in a house with a flooded basement and just four characters living out their worst nightmare and being in a totally helpless situation.

In my discussion with Jules and Ben, we talked about the season as a whole but really drilled down into what it took to create an episode shot in a way that makes it an outlier from the rest of the season while also being integral to the storyline the show is telling.

The Contending: The Old Man plays like a modern-day western. Was this planned, and did it affect how you approached the material?

Jules O’Loughlin: It was spoken of a lot before we started shooting season two. Jon Steinberg/our chief writer and showrunner, and Dan Shotz/our showrunner, spoke about the idea that the opening gambit of Chase and Harper in Afghanistan should feel like a Western–two guys on a mission. So we talked a lot about that and looked at many references from photographs to films. Zoe Neary, one of our producers, often does that, and she works closely with John Steinberg, then with the director–in that case, it was Steve Boyum–and myself, and would fire references across, and then I’d shoot references back. So we’re all getting into this headspace. Yeah, it’s a western for Eps one and three this time because we go away from Chase and Harper in two. One and three, let’s play it as a Western. Spot on, you nailed it; that was the feeling we were trying to evoke.

Ben Semanoff: I was just going to add that those episodes were nearly complete when I came into the fold. Honestly, episode 5 is a bit of a bottle episode. I never really had any conversations in terms of trying to weave in any bit of the Western genre into the show because I think for the very fact that it was a bottle episode. It gave Jules and me the sort of room to play and stretch in terms of the aesthetic for that particular episode. And I dug that, but certainly, as a fan and having watched the first few episodes, I can completely agree and see that was really a genre they looked to emulate and did a great job of it.

The Contending: Episode 5 is my favorite episode, and we will dig into it.

Jules O’Loughlin: Mine too, and I think it’s a lot of people’s favorite episode.

The Contending: How do you make California into Afghanistan, Jules? Afghanistan is known for its caves and rugged terrain, which is why empires go there to fail.

Jules O’Loughlin: They call it the graveyard of empires, don’t they? But it’s really interesting; just a bit of backstory in season one: on Friday, the 13th of March, 2020, we were shut down because of COVID with a whole bunch of productions worldwide, mainly in America and Britain. But that was the big date. Two days later, we were due to fly to Morocco to shoot the second half of season one on The Old Man, the first half having already been shot in the United States for all the stateside material over the eight episodes. And then, when we returned later in the season, we were all on hiatus over those ensuing months. It was like, we can’t go to Morocco, even though we booked out this entire hotel in Marrakech for a couple of months and then paid all the money, and I brought in with the high crew my old crew from Black Sails in Cape Town, and everything was ready to go and of course, shut down due to COVID. Over the ensuing months, I thought Morocco would be difficult because of COVID logistics, so we can’t go to Morocco. So where else can we go? And I was talking to Dan Shotz, the showrunner, about shooting in the deserts of Australia, where they shoot Mad Max out of Broken Hill. Then I was thinking about various other places. Then, we took a look at Santa Clarita. They went and looked at locations and went up to Blue Sky Ranch, which is a famous movie ranch, where they’ve shot movies and TV shows. We can build sets there, but then there’s the issue of the mountains. What do we do about the mountains? We’ve got a fabulous VFX super, Erik Henry, who I’ve been working with since the days of Black Sails back in 2013, as have Dan Shotz and John Steinberg. And he said listen, I think I can make the Sierra Nevada mountain range look like the Hindu Kush. And when I heard that, because I’ve traveled a lot in northern Pakistan, right through the Karakoram range, I just went bullshit, mate. There’s no way you’re going to make the Sierra Nevada look like the Hindu Kush in the Karakoram.

But I hadn’t been to the Sierra Nevada. And I didn’t realize that this is a very new mountain range like the Karakoram and very jagged. So we built sets in Santa Clarita, which were amazing. Then, I finally saw the end result when the show aired. I saw a few testouts of the VFX and was blown away at what Erik had done with that mountain range. It was brown, and it was dusty, like Afghanistan, and it had these big snow cap peaks. So I thought, what a phenomenal job. But cut to the beginning of season two. We go back to Santa Clarita to do Chase and Harper, now and now, modern-day going back there. And we arrived after there’d been a lot of rain in California to find not the foothills of Afghanistan but the rolling green hills of Ireland. It was so green. Then we faced the next crisis: how do we make this look like Afghanistan? And through the power of modern grading, mostly, and some VFX work, we shifted what was green terrain into, once again, Afghanistan. As I always say, the camera lies at 24 frames per second. (Laughs).

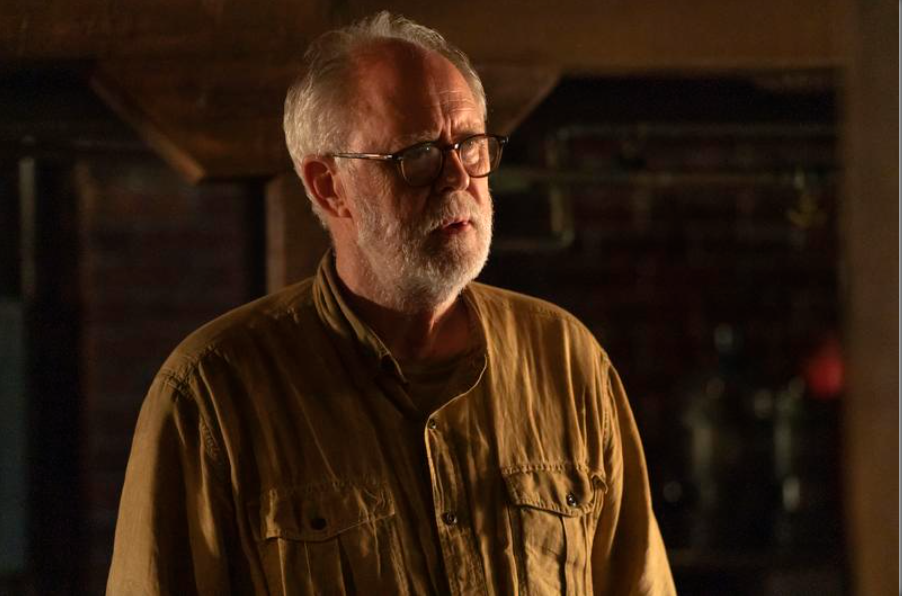

The Contending: With Bridges and Lithgow, as Chase and Harper, there is a strong feeling that both of these characters are aging out of this business and, for different reasons, they are staying in it to save their adopted daughter, Angela (played by Alia Shawkat). So when you’re shooting these two folks, these extraordinary veteran actors, do you just put the camera on them and watch them play tennis? (Laughs).

Ben Semanoff: Those two actors are unbelievably collaborative performers with each other and everybody around them. Sometimes, you see performers who shut their eyes and forget they’re working on television or in film. They do what they do. They act how they act without any consideration for what the camera’s seeing. And it’s amazing because there were times when Jeff or John would be open to choices that Jules was directing. I remember one of our first days in the big living room set where they were going to have the phone call with Emily in Afghanistan. Jeff comes in, and he is just so excited. He is filled with juice. He wants to have fun and play, and his ideas are rolling. And he said I had this idea to come over and sit at this table. He goes over to this table jammed in the corner of the room, sits down at the table, looks up at Jules, and says yeah, this is a bad idea because there was no way to light him in the corner of the room.

But he gets it. He plays, and he’s open to suggestions. And yeah, you could probably point a camera at those two and get gold without saying or doing very much. But what would be the fun of that? Often, they both came in loaded with ideas about how they saw the scene and how they wanted to execute it, but just as equally excited about any ideas that me or Jules, or honestly anybody that was in the room, would offer up and willing to experiment with those ideas to see if they had value and how they would inform whatever scene we were trying to perform at the time. It’s some of the most fun I’ve ever had as a director working with those two actors.

Jules O’Loughlin: You’re always looking to create a safe place for the actors to work in. And you’ve got these two most incredible actors, and there’s nothing better than just sitting there and watching two actors of this caliber kind of riff off one another. You want to make it cinematic, but you also want to make it a great environment for them to do their thing. These guys have been around for so long, and they’re so experienced that we could have locked them in a fridge together. (Laughs). If they thought it worked for the scene, they would do it. It’s never. No, I can’t do that because you’re interfering with my process. If we’re respectful to them, they’ll go on the journey and do anything for us if it works for the story, and that’s the beauty. I think you’re right to say, Ben, there’s a lot of mutual respect with those guys.

Ben Semanoff: And I think antithetical to what you might expect, there’s no ego. You’re working with these two unbelievably seasoned actors that we all have been watching for the past 40 or 50 years. And they each individually have more experience in this business than Jules and I combined, and they walk in with no ego. That’s a really refreshing experience, this idea of them yearning for you to share and contribute and offer something they can play with. And the two of them together are remarkable. I think you hit that on the head, Jules. I think the young performer is not always as receptive, not just to ideas that the people around them offer, but to things that the actors in the scene with them are doing. That’s what a seasoned performer can do: forget about their intention and watch and listen to the performers in the scene with them so they have something to react to. Those two, it’s like they’re jamming.

The Contending: I do want to speak, Jules, to what I would say is the most significant action sequence in this season, which is the chopper attack in episode three. It has that potent mix of disorientation and what a battle scene feels like. How difficult technically was that to shoot? Did you feel like you got the sort of propulsive feeling that you were looking for in that sequence?

Jules O’Loughlin: There’s a couple of things going on with it. One is that it’s the first time that we become, not unintentional, the show is very intentional in how the camera works. But it’s often quite languid. It follows action, lets the action go, and then catches up to it again. It’s like we constantly say it’s the Old Man. The camera has to be infused to a certain extent with that feeling. The firefight in episode three is the first time where that goes out the door, and it becomes pandemonium. And it’s fast cutting, action, and all that stuff. But as far as the technical side of it, it’s not as chaotic in the filming as it looks in the realization of it. It’s very planned out. It starts with the director, Steve Boyum. A little backstory of Steve: Steve used to be a stunty, and then he became a second unit director and then a main unit director. In Apocalypse Now, when Lance (Sam Bottoms) is surfing off Charlie’s Point, the mortar goes off, and the guy on the surfboard falls off; that’s Steve Boyum.

He’s been around for a long time. He’s done a lot of battle scenes. It really starts with the script, and then he’ll have the whole sequence storyboarded. We go into previs (previsualization), and then from previs, we start working with our stunt coordinator and our special effects guys, and you just go by the numbers. What are the action beats, what are the story beats, what do we need to cover, what do we need to blow up, who’s firing at who, where are the camera angles, and how many cameras do we need? We wanted it to feel chaotic. We wanted it to be handheld. I usually am an operating DP, except in North America, where I don’t operate. This scene was the first and only time in the season that I had a chance to get back on the camera again, which was a lot of fun. But yeah, you have a checklist of things you’ve got to do and angles, and you just go through it by the numbers, and it takes quite some time. Having to reset for explosions or gunfire is time-consuming, and overhanging all of it is safety. Everyone has to be super safe. And so, while it looks chaotic on screen, it’s very measured, thought out, and scheduled to the nth degree. And as I said, safety comes number one on the list.

Ben Semanoff: We didn’t have much in the way of action scenes in episode 5. When I got the script, I was a fan of the show. What is great about the show is that it’s not entirely dependent upon all these unbelievable action sequences to carry the story. But, as a fan of the show, I was okay, cool, I’m going to do an episode of The Old Man here, there’s going to be some action, and then I get episode five, and I’m like, wow, it’s four people in a house. (Laughs). But I do have to say again, as a fan of the show and having watched the first few episodes, that helicopter sequence was just breathtaking. I remember my jaw dropping when that helicopter revealed itself. It was stunning.

The Contending: We are going to get to episode five now. As you say, it’s four people in a house, a house with a basement that is flooding, which I thought was fascinating, because they come back to Lithgow’s home, and his wife is dealing with one of the most domestic issues that a homeowner could have, which is your water heater. There isn’t action at all in that episode. But there is a phone call. I thought the shooting of that sequence, with Angela’s two substitute fathers in the room while she is under siege. The tension in the cutting, shooting, and darkness was as nail-biting as any action sequence you could create because of the helplessness of Lithgow and Bridges’ characters at that moment.

Ben Semanoff: As a director, the juicy stuff is the drama and less the action. The action’s just fun. And certainly, initially thinking, there’s no action here, that was my knee-jerk reaction. But boy, to have an opportunity to direct those four amazing performers in essentially a one-house play was exciting. And yes, the super simple domestic problem in the basement was a beautiful metaphor. I thought the idea that this world that Harper had created, from which he had sheltered his wife and family, was starting to leak and burst from the inside out. But then, for a number of reasons, I thought this imagery of the water could help us from a technical standpoint, but it could also help expand that metaphor that it feels like not just from the inside out, but from the outside in–being consumed by water. Anybody that’s dealt with a water leak knows that it’s pervasive. You don’t just chew up some gum and stick it in a hole, and the problem is solved. It’s like the cartoon where you put your finger in the hole, and it stops the water leak, and then it bursts from somewhere else. And so that was the idea of incorporating the rain. Beyond that, I think that scene was originally staged in the script in a really small, dark room that had one window. And on top of it all, amid that scene, the power goes out. From a purely technical standpoint, Jules and I said we won’t be able to see anything in this tiny room.

From a directing standpoint, I thought, wait a second. It’s seven or eight pages of script. They’re on a phone. The most horrific possible thing that could be happening to them is happening to them on the other side of the phone. They have no control over it. My main job is to dramatize or physicalize emotion. If you’re going to put four people in a box around a phone, it’s hard to physicalize emotion. Jules and I instantly had the same reaction: we need to move it out of this room; it’s got to be in a place where the actors can get up and express themselves physically. They can get themselves away from this phone where this horrific thing is happening to their daughter and come back to it with urgency and anticipation of how can we possibly help? Jules and I, both being parents, have experienced that vulnerability. Being a parent, you have this idea that you can protect them from everything when, in reality, it’s completely futile. You have no real control. You can try to put things in motion to protect them. But when push comes to shove, you have no control over their destiny. I know there’s been some criticism, probably from the action fans of the show, that you don’t get to see what’s happening on the other side of the phone. I get that from people craving the action, but for people understanding and relating to the parent’s experience, that is exactly what goes on. You’re on the other side of a phone, and you have no wherewithal to help your child. Blinding us and them from what was happening on the other side of the phone was a really interesting dramatic tool. I think Jules shot it beautifully. It was Jules’ idea to add the rain outside, which helped us look out those windows.

Jules O’Loughlin: I said earlier that episode five is my favorite ep, and it’s my favorite for two reasons. One is that I got to work with Ben. Ben used to be a world-class camera operator and did a lot of movies and big TV shows. When I first found out that my director used to be an operator, my first instinct was whether he was going to stay in his lane.

Ben Semanoff: Did I? I don’t know if I did. (Laughs).

Jules O’Loughlin: But it was only for a brief second because I knew that he would understand a lot of what I was talking about, everything I was talking about in so far as camera. And it was a lot of fun. He was a great collaborator. And it’s not just about the camera. Every day we would go wow, shit, we didn’t know that about Ben. He knows about liturgy, he knows about art, he’s a diver, we went to the firing range, he knows about weapons, he knows about so many different things. We would say this guy is a poet warrior. Every day was a new surprise. He’s not just a director; he’s also all these other things. And he is very intuitive when it comes to storytelling with the camera. And without a word of a lie, I have had people come to me and say not only is this my favorite episode, but the craft of this episode is top-notch. What were you guys doing? It’s Ben Semanoff. I was hanging out with him.

He brought so many great things to what we were doing with the camera and the story. The hot water system leaking was one thing, but Ben’s idea was to create a nightmare for all of us and have a flooded basement. With that flooded basement, of course, comes all this reflection and spectral highlights. Every day in pre-production Ben would bring these multi-layered elements to this episode. The other reason it’s my favorite episode is because it’s such an emotional episode, and I got to tell the story. It’s an emotional journey, a real emotional journey for these characters, but it’s also a journey of light. When I first read it, apart from the opening sequence, which is the Afghan montage funeral sequence, I thought the rest of the episode would be challenging. There are no free shots in this episode. I’m walking into a black box every day, and I’ve got to turn on the first light and work from there. I’m going to be able to paint a lot with light and hopefully support and drive the story with what I’m doing with lighting. And I was able to do that. Ben gave me the freedom to do that, and he helped me with so many of the ideas as well. We would spitball constantly. It was a rewarding experience, which shows in the end result.

Ben Semanoff: what’s amazing about the episode as a whole, because I was trying to focus my answer onto that one scene in the living room, was the partnership with Jules and this idea that I really think of filmmaking, particularly the camera as a language. Every shot, whether it moves or is static, whether it’s low or high, whether it’s close or far from the performer, it says something. It tells a story on its own. And to have a partner like Jules, he got it. Every time I’d say no, I want to be over here, he’d understand why, what that was saying about the story. And then, of course, to take this house, which, for the most part, we shot during the day. We have two extraordinary actors, but they’re in their seventies. They don’t want to be working nights. (Laughs). Nobody wants to work nights.

So we take this house that we’re shooting in the day, tent it, and make it into this black box. That’s what people don’t realize Jules had to do. He had to eliminate all the light and decide where to add the light. From the beginning, I kept saying to Jules, I feel like this is like the house on a hill. It’s a bit of a horror movie. I want to lean into the horror of it all. And he got it, man. He ran with it in terms of creating dark and moody environments that made you lean in to see into the shadows. But that’s essentially what these characters were dealing with. The ghosts of their past were all around them. In particular, there’s one shot, the long shadow of Harold Harper coming up the wall as he came upstairs to sit and have this conversation with the ghost of his son–Jules just killed it. I’m just lucky that I had Jules, who got it, and the entire team, from the production designer–who had a minor coronary when I said I wanted to flood the basement of the set that was already built–to the set decorators and Jules’ entire team. They all intuited what I was going for and then added to it. That was key.

The Contending: There is certainly a fair amount of violence that takes place in The Old Man that is on screen. The fascinating thing about this episode is that two moments of violence are not shown. There is, I guess you could say, an “enhanced interrogation” sequence with Jeff Bridges and a would-be assassin in that dank, wet basement, and you see none of it. This is not 24. There’s no Kiefer Sutherland taking a screwdriver and putting it into a guy’s knee, but there are the showing of tools and a little screaming. Then there’s that incredible overhead shot of Bridges walking across the basement with the saw in his hand, essentially, to put it back—how polite. The shooting of that sequence, to not show you the horror and the brutality of it, was somehow more horrifying.

Semanoff: I think Jules and I agree because I think the two of us have very similar tastes and aesthetics. It’s so much more interesting if you can activate the audience’s imagination; it will be so much more powerful. They’re going to be engaged in the story in a way that you can maybe do with visual effects, stunts, and photography, but honestly, I think the human brain is perhaps more violent and gory than we could ever even show. The idea of thinking whoa, what’s up, what’s happening? We’re watching Lithgow walk back up the stairs as we hear the sounds of the prisoner being interrogated. I remember watching the scene with my wife the other night, and they added those sounds. I even turned to her and said I wish they hadn’t added those sounds because it’s almost like we get it. We know it’s going to happen. The more we can leave to the audience to create in their minds, the better. If it had just been the chair being dragged closer to the prisoner, that would have made my skin crawl, but I get it. They wanted to make sure they answered the question for the audience. And the question is, what’s he about to do? He’s about to interrogate this prisoner. But the more we can get the audience to lean into storytelling, the better.

Jules O’Loughlin: I often say to a director, let’s make the audience work for it. Let’s not start on a wide shot and go boom, here we are. Let’s start on a glass and develop off the glass and who’s picking it up. Okay, there’s some lips drinking it. Where are we? Who is this person? What’s outside the frame? I remember years ago, probably when I was at film school when I saw Witness. There’s this great shot when Harrison Ford’s talking to his boss, and he’s in a phone booth, and the camera is on the back of his head, and it’s the realization that his boss is the bad guy. Peter Weir just plays the whole thing out on the back of his head until the final moment when Harrison Ford turns to the camera. To me, that was just genius. Let’s not be here; let’s be here. Let’s put the audience in his shoes. Let’s make them work for the information. Audiences are smart, and I think sometimes we can tend to dumb things down for them. It’s not what you show, it’s what you don’t show, it’s not what you like, it’s what you don’t like. That’s a powerful thing. It’s what you don’t show that really counts.

The Contending: That scene also makes me think of Michael Mann, who often shoots actors from behind. There’s a scene in Miami Vice where the head of the cartel is shown that Colin Farrell and Li Gong’s relationship is beyond what is acceptable to him. All it does is show the camera closing in on the back of his head, and the tension is extraordinary. I love that you are being asked to watch a character think and not be given their face, which is a fascinating choice.

Ben Semanoff: And you’re also, from the audience, craning your neck to figure out what’s happening on the other side of their head, right? What is the emotion? It’s so much better to finish a scene and have the audience go oh, I don’t even know what the hell that person’s feeling. That’s where you want the audience when they exit a scene so that the question gets answered in the next scene or the scene after that. If they leave a scene with all the questions answered, there’s no anticipation for the next scene. There’s no demand for more information. That’s what’s so great about that. If only, when I retire, there’s a shot named after me, like the Michael Mann shot. On Ozark, we used to do the Michael Mann with an answer—or maybe not the answer–but something extra. You’d be behind the character at the end of the scene, focused on the back of their head, and that person they were talking to would be walking away. Then they would turn just a little bit so you’d catch a glimmer in their eye or something. It just gives you something to go about: what are they thinking and cut to the next scene. You want your audience in that pocket.

Jules O’Loughlin: We did some of that with Lithgow when he’s talking to his son and looking at the photo.

Ben Semanoff: Oh yeah, for sure. That shot of him in the reflection, it worked so great just to overlay that image of him looking at himself, but that three-quarter back on him and just, if you’re right behind, you don’t quite get enough, you open it up just enough to see a little bit of face. Then, suddenly, you’re engaged, and you’re leaning and doing the Rosemary’s Baby thing. Who doesn’t talk about that where you’re craning around? Is there any way I could possibly get a view in that room to see what’s happening on that phone call?

Jules O’Loughlin: Just a funny anecdote I had when I was doing The Hitman’s Bodyguard, we did this shot from behind Ryan Reynolds’ head, and the producer came up to me and said, listen, are you going to get a close-up? And I said no, that’s where we want to be for the scene. The producer said we paid 15 million bucks for Ryan Reynolds. I said you paid for the back of his head as well, didn’t you? You paid for the whole thing. It was a funny moment, we laughed. I don’t remember if we ended up getting that close-up or not. You paid for all of it. You pay for the body language, all of it.

Ben Semanoff: A great actor can do such subtle things with their physicality that tells the story without looking at their face. It’s amazing. It is a challenge when you have a producer hovering. Aren’t we going to shoot this? But I think you said something, Jules; it’s a credo that we both operate under, which is that it’s not what you shoot; it’s what you don’t shoot. Those are the choices that define. I remember being in an art museum in London with my family and looking at these paintings that, when you stepped up close, were just a handful of brush strokes that described this unbelievably beautiful scene. From afar, you wouldn’t have noticed. You walk in and go, wow, that person in this scene is like seven brushstrokes. That’s all they are. And that artist could have said I’ve got to refine this. I’ve got to add this. I’ve got to add a little detail to the nose. I’ve got to mix it. But they didn’t. That’s how I look at our craft. What is the least amount of work we can do to tell the story and allow the audience to fill in the rest?

The Contending: Minimalism certainly has maximal value, often. Do actors ever say, when you choose to shoot from behind like that, “How do I act if I don’t get to use my face?”

Ben Semanoff: It’s funny. Actors are different. One of the first times I experienced this, an actor understanding the ability to withhold their face from the audience, was with Ben Mendelsohn on a show called The Outsider. At this point in my career, I was just starting directing, but I was operating camera on that show. Ben sat in this interrogation room with his hand over his face for 90 percent of the scene. I said to him, Ben, we can’t see your face. He said I know; I’ll let you see my face when I want you to see my face. I’ve worked with other actors where I’ve said hey, I’m going to put the camera behind you. If you want us to see your face, you can open up to the camera. I’ve had performers, and really seasoned ones, say, I don’t know what you’re talking about. If you want to see my face, put the camera where it sees my face. No, I’m trying to give you the power and control, and then at some point, you go, okay, this performer doesn’t quite understand. That’s fine. But then you have performers asking if you are going to shoot the close-up. I wasn’t planning on it. Okay, this is an awkward conversation. It’s tricky to navigate, for sure.

Jules O’Loughlin: I’ve done that shot from behind quite a few times, and I’ve never had an actor go really, you’re doing that? I have had actors and stars, like real movie stars, who have said really? Do you need a close-up? Do you really need a close-up? It was like oh, okay, that’s interesting that you would say that. When I’ve done it, the shot from behind has always been this conversation with the director and we’ve spoken in these kinds of terms of why don’t we do this and make the audience work for it? I’ve never had pushback from an actor about that. But they’re all different, like different things, and have ideas sometimes. And sometimes they don’t. And it’s in your hands, guys; you do what you need to do.

Ben Semanoff: That’s exactly right. They’re all different. The trick is figuring out who you have in front of you and what willingness they have to play or not with the filmmaking of it.

The Contending: I love the idea of Mendelsohn telling you you’ll see my face when I want to show it to you. To ensure that we cover Jules’ work on the show, I want to talk about episode seven, the street sequence from the embassy with Amy Brenneman. I love to say that Amy Brenneman’s character in The Old Man is a more active version of her character in Heat, where this man took her in, essentially kidnapped her at a certain point, and decided to go along. Only in The Old Man she has a lot more agency. The way it’s seeded is that she has a particular experience with firearms, and what’s happening below on the street is triggering her need and her expertise to defend herself. That almost voyeuristic shot of her looking down and discovering the trouble she’s about to get into, I loved that perspective.

Jules O’Loughlin: This was an actual location that we shot in Pasadena. We looked at a bunch of locations, as you do, to see what fit the beats of the story, and there are a lot of beats in that sequence of her going into the British police station and then the assassin coming in and sightlines and all those kinds of things. It was a real jigsaw puzzle. We found this location, which, funnily enough, had a chapel inside. I can’t remember where it was or what it was, but it had this massive chapel right in the center of it with this incredible organ, and then around it were all these offices. We had to build a little bit on-site. We had to put that wall in the corridor that she goes down into the safe room where she finds the shotgun. We had to add a couple of other walls and take a few things away, but that window that she looks out, that’s the actual window of that office where she has that interview with the CIA agent. And so we just shot that view up to the window of her looking out from the car park down below. There wasn’t any trickery to that at all. It was the actual window itself, which is rare to do something like that. You would create that shot. Here’s the trickery. The view up to Amy Brenneman was shot at the location where we shot the interior, but the view outside, the exterior, was a different location. So there’s a little movie trickery there. And that exterior location had to satisfy a few things because it was supposed to be in a rural town.

The Contending: Working on a series differs from working on a film. When both of you are passing the baton, whether it’s from the director of photography to another director of photography for an episode, because television typically moves faster than film, or as a director passing the baton to the next director, what kind of conversations do you have with that person who you are passing to?

Jules O’Loughlin: It’s actually not as difficult as one would imagine. I would say that you’re shooting the same characters. You’re shooting somewhat similar locations often. It’s the same writing. You tend to use similar lighting units, the same gaffer, and the same crew as long as you’ve got a roadmap at the show’s beginning like this is the show we’re making. It’s much harder in Ep 1 of Season 1 to do that. You often go in with ideas, and over the course of the first few episodes, the show is putty in your hands. You squeeze it, and then it’s extruded out through your fingers, and that kind of magically becomes the show. So then, when you set it up as a DP and pass the baton to the other DP, you’re having conversations with that person along the way.

They’re coming to set, and they’re coming to the monitor, and you’re talking to them, and you’re saying this is what I’m doing because they’re interested in what I’m doing, and I’m interested in passing that information along. So by the time episode two, and the next block, takes over, they’ve been watching all the dailies. They’ve been having conversations with you, and they know the road map you’re going on. So it’s not as difficult as it may seem. And then I always say, you’re the DP of episode 2 or 4; put your spice into it. This is the show, but put your mark on it. It’s the same as when I work with a new director. You’ve seen the dailies or season one; what do you want to do? If we go too far, the showrunners always rein us in a little bit. We get overexcited, but more often than not, they’ll go with it. I always say this is where we’re going. You’ve seen what we’ve done before. Now, take us on your journey, and add the spice that you want to add to it.

Ben Semanoff: There’s not much discussion between the guest director and the next guest director on the show. Jules makes a good point. It’s certainly different from season one to season two or subsequent seasons. In season one, you often don’t have a roadmap. That can be tricky, and it can also be liberating. You have a sense of what they’re looking to do. You have maybe a bunch of references. If you’re doing season one, you rarely get a look at a completed episode before you’ve really gotten into the trenches. That’s quite liberating in terms of being able to do you. Talking to other directors, the director that just preceded or followed, doesn’t happen a lot unfortunately–or fortunately. There can be some conversation when there are overlapping things storywise, maybe something that you’re continuing from a prior episode. Sometimes, you might have a conversation that circles the idea that you’re going to set this up for me and that I need this or that in play to execute the scene that I have written for me. That might be the extent of the conversation.

I think directors like having fewer guardrails. I know I do. What bums me out is if I have anybody, whether it’s a camera operator, a cinematographer, or anybody, say, “Oh yeah, we did that sort of thing on the last episode. It doesn’t matter to me; this is what I want to do in this episode. Not knowing is better than knowing because it frees me to make the choices. You want to do your thing. And, often, if somebody points that out and says, “Oh, we did that in the last episode,” I don’t think it’s the same thing. I’m sure it’s not the same thing, and you watch the episode, but no, it’s not the same thing. Just because we staged the scene in a similar area of a set doesn’t mean that it will have the same impact or relevance to the show. So I like not talking to people. If you have a good cinematographer like Jules, you can always lean on them from a dramatic standpoint and say hey, does this fit with the show’s aesthetic? Or is this what I want to do? What is this show’s version of that? And can you give me some feedback so I can make something that fits in the world of The Old Man or whatever show you’re on.

![We Could Go See BOOP! And Predict the Tony Awards! [PODCAST]](https://thecontending.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/tonys-120x86.png)