Netflix’s Adolescence has become a sensation for how it turns on the light in a darkened room. It shows that even the best parents can witness their child do monstrous things when communication goes by the wayside. The family at the center of this limited series, The Millers, could one thats lives down the street from you, and it doesn’t necessarily matter if the series was set in the UK, the United States, or another country around the world. Once the monter under the bed has become a friend or an ally or a confidant, it’s hard to push it back under the bed. Writer Jacke Thorne dove head first into the alienating world of the Mansphere, and he created a series so vital that it feels like danging off the side of a cliff.

Thorne continues to explore how young people come into their own, and his resume is packed with stories that have youngsters at the center. Enola Holmes‘ circumstances vary from His Dark Materials or Wonder. He wrote the script for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child on stage, and his next project, Lord of the Flies, looks like it will explore a different kind of anger in young people. Does Thorne search out these kinds of stories?

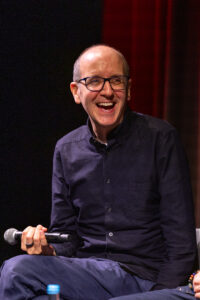

“It’s something that I am always trying to figure out,” Thorne says. “I wasn’t very good at being a teenager, and so I am constantly trying to understand why I wasn’t. For a lot of us, the teenage years are the hardest years of our lives, so trying to shed light on that time feels like an important and interesting thing for my writing to do. I have “Be Good” [tattooed] on my wrist because of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. E.T. helped me feel better about myself and the film made me feel like I had hope in this world. The ages between ten and twenty is the era that I keep returning to, and the new Lord of the Flies has got forty kids between the ages of six and thirteen.”

As we spoke about childhood, Thorne commented on the framed illustration of Mr. Rogers that hangs in my podcast room.

“You’ve got a reflection of childhood coming back at you all the time,” he says, with a smile.

When Adolescence first dropped, a lot of audiences assumed that it was going to be a whodunnit style mystery. We have grown accustomed to binging shows that tease us with the possibility of discovering the “who” while Thorne’s series is more interested in dissecting the “how” and the “why” and, probably most important, “can we prevent this again?” Most impressive, I think, is how Adolescence doesn’t give you all the answers.

“It was all about subverting that, but it was also about meeting the one-shot,” Thorne admits. “From the start, I was thinking about the grammar of our storytelling, because the grammar has to be different from every other show that I’ve previously written. Otherwise, the one-shot would be exposed, and the writing had to meet the style. If we tried telling this story in a conventional way, I think we’d have ended up exposing our process a little, and then we might have had other questions about the circumstances of the story. It would be so partial or incomplete, I think.

Stephen [Graham] and I discussed how we aren’t going to answer all the questions that we ask. By answering the biggest question from the start freed us from that. In episode two, Bascombe is going after a knife, but he doesn’t find it by the end. In episode three, I toyed with putting something in the script that explained where the knife was found since it would have been possible to sneak it into the conversation between Jamie and Briony. That felt inauthentic, though, and that’s deliberate. That’s how that life works.”

Thorne casually mentions that his social media is slowly getting back to normal after wandering around in some dark corners before he reveals an inspiration in another show in terms of how hour-long storytelling can be brought to an audience. There is nothing standard with Adolescence.

“All my social media is still flooded with the Manosphere from when I was researching the show, but now it’s that mixed with Meryl Streep and Martin Short,” he says, with a laugh. “There is some joy trying to come back in [now]. I was obsessed with WandaVision not just because it was a great piece of storytelling, but because I was obsessed with how it worked. I don’t think that show gets the credit it deserves for really challenging the grammar of television. It made us sit forward, and, in a weird way, it was a huge inspiration for Adolescence. Obviously, our show is nothing like a Marvel show, but the scraps of information that you got where you were slowly piecing together the story was so compelling. It forced me to put my phone down and really concentrate. That’s the sort of show that I want to make now.”

You cannot help but think about anger as you watch these four episodes, and those thoughts could change from person to person. Did Jamie’s parents, Eddie and Manda, every consider that their young son could harbor so much anger? Is anger learned? Do we subconsciously absord that rage from our elders in person as well as from a computer or phone screen? I couldn’t help but think about how Eddie is now self-conscious or aware of every time he raises his voice now that his son is locked away.

“There are two things at play, and the first is what Jamie’s learned himself,” Thorne explains. “The second is what Jamie’s been taught, and a lot of the response to the show has been sort of saying that Jamie is a response to the Manosphere, to incel culture, and things like that. Jamie is actually a response to his schooling, his friends, his family–he’s a response to all these different moments in his life in addition to the things that he’s consumed online. The things that he’s consumed online only make sense to him since they are the experiences he’s had. What we were trying to capture spheres of blame and understanding of what he’s learned through his life. I think his anger is probably something that he’s witness a bit too often from Eddie. Jamie’s thought process is not like Eddie’s, but the way he snaps is like him.”

That anger is then presented in a different way when Jamie is away from his family, and it hurls out of him towards Erin Doherty’s Briony.

“When I was writing episode three, I was trying to write a boy that was trying to hide himself and hiding who he truly was from someone that he really liked,” he says. “Jamie admires Briony and enjoys her company, but he’s trying to hide so many truths from himself. It seeps out of him. The hardest bit about writing that was trying to capture the fact that this has got to be mostly about someone presenting an image of himself rather than someone that’s telling the truth about themselves. Little drops of truth come out in small places.”

When you are finished with Adolescence, we walk away from The Millers with knotted, complicated feelings. Jamie has accepted his reality, and he will not grow up with a constant, traditional parental figure. After Thorne left these characters on the page, though, his thoughts and feelings stretch out to two young, female characters. Thorne reveals that he will be thinking about these young women for quite a long time.

“They’re all also inside the hamster wheel,” he admits. “But the person I think about a lot, in the Miller family, is the sister, Lisa. I worry so much that she will still have an opportunity to be herelf. When you’re my age, or Stephen’s age, you’ve got an opportunity of something you’ve been to go back to. She’s still so plastic, so unformed, and the idea of being trapped as being Jamie’s sister forever is really tough for me to think about. Lisa, who is played by Amélie Pease, is so special in lots of ways. She’s wise, and she save sthem from their little hole that her and her parents are in. I also think about Jade and Ryan a lot, too. I worry that Jade could get lost, because she’s so heartbroken.”

Adolescence is streaming on Netflix.