The story of a young high school-aged person falling into the wrong crowd and down a rabbit hole of drug abuse and premature sexual activity is hardly an uncovered subject, but as Roger Ebert once said, “It’s not what a movie’s about; it’s how it is about it.” And boy is Good Girl Jane ever “about it.” Sarah Elizabeth Mintz’s remarkable feature film debut isn’t just about a girl in trouble; it’s also based on her own life. Good Girl Jane is a very personal and bold film by any director, let alone a first-timer.

The film expertly shows how a girl caught in that awkward age between child and adult can fall into the wrong crowd due to loneliness and displacement. As Mintz’s “Jane,” newcomer Rain Weaver (in her first role with lines) carries the film more than ably on her slim shoulders. Weaver is in every single scene of the film, and her journey from sullen teen to troubled teen to hopeful teen is handled with great, naturalistic skill. If all is fair in the world, both Mintz and Weaver will go on to have long and significant careers.

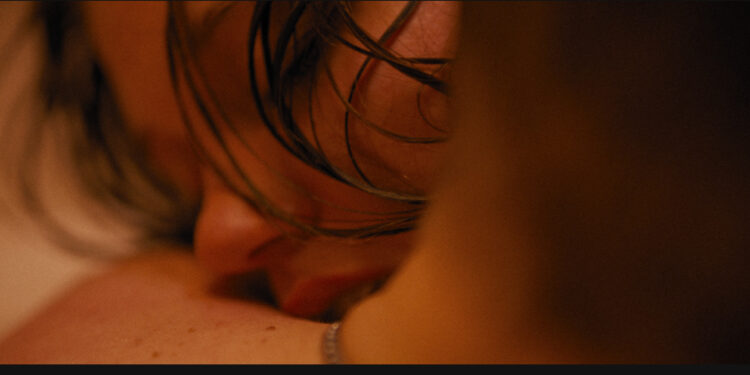

In searching my mind for comparables to Good Girl Jane, I came up with only two that share this level of authenticity and fullness of delivery: last year’s Independent Spirit Award nominee Palm Trees and Powerlines and Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen from way back in 2003. What makes the difference from the average cautionary tale to something much greater is the intimacy and immediacy of the telling. Mintz’s camera takes you in so close that you feel like you are eavesdropping during the film’s quieter sequences. When the more chaotic scenes occur, your discomfort is ratcheted up to the degree that you almost want to escape, but the movie is so riveting and well-told that you can’t help but be transfixed.

Good Girl Jane feels like a movie that has been lived (and according to Mintz, it has), which makes the viewer lean in, even when disturbed by the stew that takes a girl from safety to grave danger. That stew consists of discomfiting change (Jane moves to a new school), bullying, divorced and not fully present parents, and a desperate need to find something/anything to break the cycle of loneliness that Jane suffers from. As Jane’s mother, Ruth, Andie MacDowell gives a standout performance even in relatively limited screen time. It’s not that Ruth doesn’t care about Jane–she does. But Ruth is trying to single-parent in a far too minimal fashion. She chides Jane’s habits, choice of music, and appearance, but for all of the exhausting criticisms she has for Jane, she does not truly see her daughter. Her preoccupation with her work and her animosity towards Jane’s father (who can scarcely be bothered to pay his two daughters Ruth’s level attention) are prioritized over Jane’s and her younger daughter’s (‘Izzie,’ well-played by Eloisa Huggins) well-being.

The genuine heartache of Good Girl Jane isn’t just between Jane and Ruth. Jane’s sister could really use a big sister in much the same way Jane could use an engaged mother. Still, as Jane meets a 21-year-old, predatory man named Jamie (Patrick Gibson in a right-on-the-money performance) who is both a seller of drugs and an addict, the attention he pays her is as irresistible as the coke and meth she starts to consume regularly. One of the more unique touches in the film is how Izzie, the youngest character, sees the trouble Jane is getting into with far more clarity than the adults in their lives. It is Izzie who convinces Jane to confess to their mother about her drug use, and in a scene that perfectly encapsulates the unintentionally practiced distance between this mother and her daughters, Ruth can’t let Jane speak the painful words regarding her addiction without checking her phone multiple times. As a viewer, it’s excruciating, and one can only imagine how brutal it is for Jane to gain just a few moments of her mother’s attention. Jane is so broken and beleaguered by this point; she’s not asking for help as much as she is simply trying to inform, and even that is almost too much for her to expect.

To her credit, Ruth does try to help her daughter, but she’s so outside the habit of doing so it’s as if she doesn’t have the tools. Only when Jane’s half-hearted effort to quit drugs and Jamie fails, resulting in high-level consequences, does Ruth’s maternal instincts kick in. MacDowell’s ever-expressive face tells you without hardly any dialogue that she has finally flipped the switch. But as with all people who suffer from addiction and who have been preyed upon, it is ultimately up to the person who was pulled down the well to accept help and then help themselves find their way out.

When Jane experiences her “crossroads” moment, the scene’s drama is simultaneously casual and palpable. The simple physical action of closing a door or hanging up a phone can mean so much more than that act itself. To attempt to leave behind a way of life that made you feel welcome when no other place did is an act of courage that no one should underestimate. As we watch Jane reach that moment, we long for her to make the right choice, to summon the necessary courage to change her life.

Jane is a “good girl.” She just doesn’t believe it. But we want to believe in her. And more importantly, we want Jane to believe in herself.

Good Girl Jane screened in 2022 at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, winning two awards (Best U.S. Narrative Feature for Mintz and Best Performance for Rain Spencer). The film world is a strange place. Being a “festival darling” doesn’t guarantee an easy release to theaters or streaming services. But the jurors at Tribeca saw, and they believed. They were right to. Good Girl Jane is one hell of a film that resonates well beyond the closing credits.